As the co-author, along with Tara Mukund and Julianne Louie, and under the supervision of Professor Alexandra Papoutsaki and Professor Daniel Epstein, we proposed a theoretical framework to support temporality, or short-term reflection, in tracking technologies, grounded in empirical data obtained from a case study on baby tracking. Our paper, published in CHI 2025, contributes to the advancement of understanding temporality in personal informatics and offers design recommendations for various applications necessitating short-term tracking, including asthma management, hydration monitoring, and more.

Role:

UX Researcher

Skills applied:

Qualitative research, interviews, surveys, thematic analysis coding, Figma.

What is Temporality?

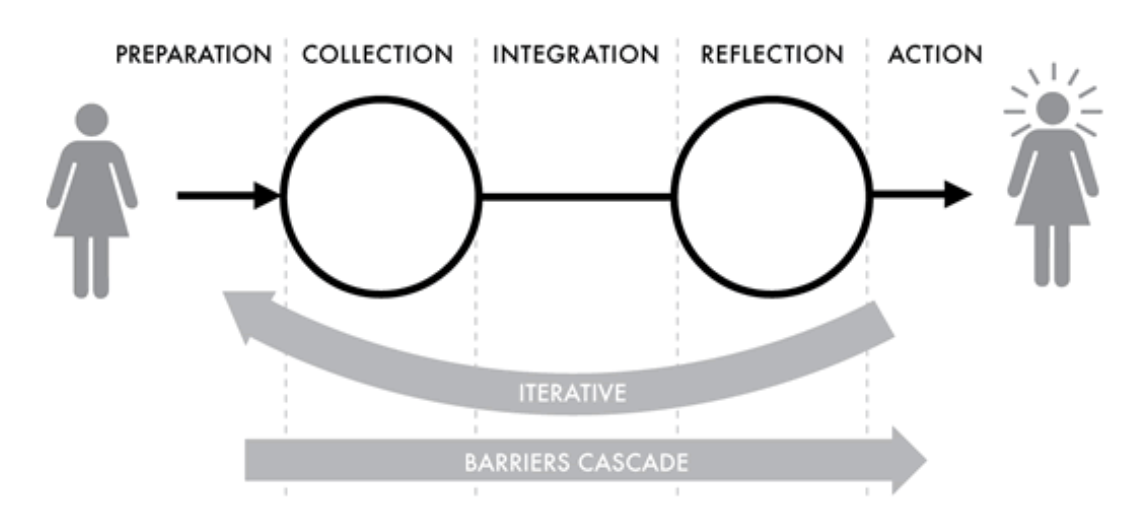

Temporality is the time that has elapsed between when user collects data and when they reflect on their tracked data. In the case of multiple data points being reflected on, it is the elapsed time between the first data point of interest and reflection.

Regarding temporality, researchers and desginers have assumed that users usually take on a long-term view of reflection, requiring multiple entries over a long time to gain meaningful insights, reach a goal, or change their behaviours. Theoretical models of reflection, in particular, do not capture the full temporality of reflection as they neglect the short term [1, 2]. In this, we lack a principled understanding of how people temporally reflect on their data, leaving unanswered what questions people seek to answer with their data and how they reflect in varying time frames.

Why is short-term reflection & temporality important?

Millions of individuals engage in short-term reflection, spanning from immediate to within a day. This encompasses various domains such as physical activity tracking, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) monitoring, hydration levels, asthma management, and chronic illness care in elderly populations with complex medication regimens. As current theoretical frameworks and design approaches in the Personal Informatics field often fall short in effectively capturing and supporting these short-term tracking needs:

How do we better design technologies to support users who track and track in the short-term?

Solution:

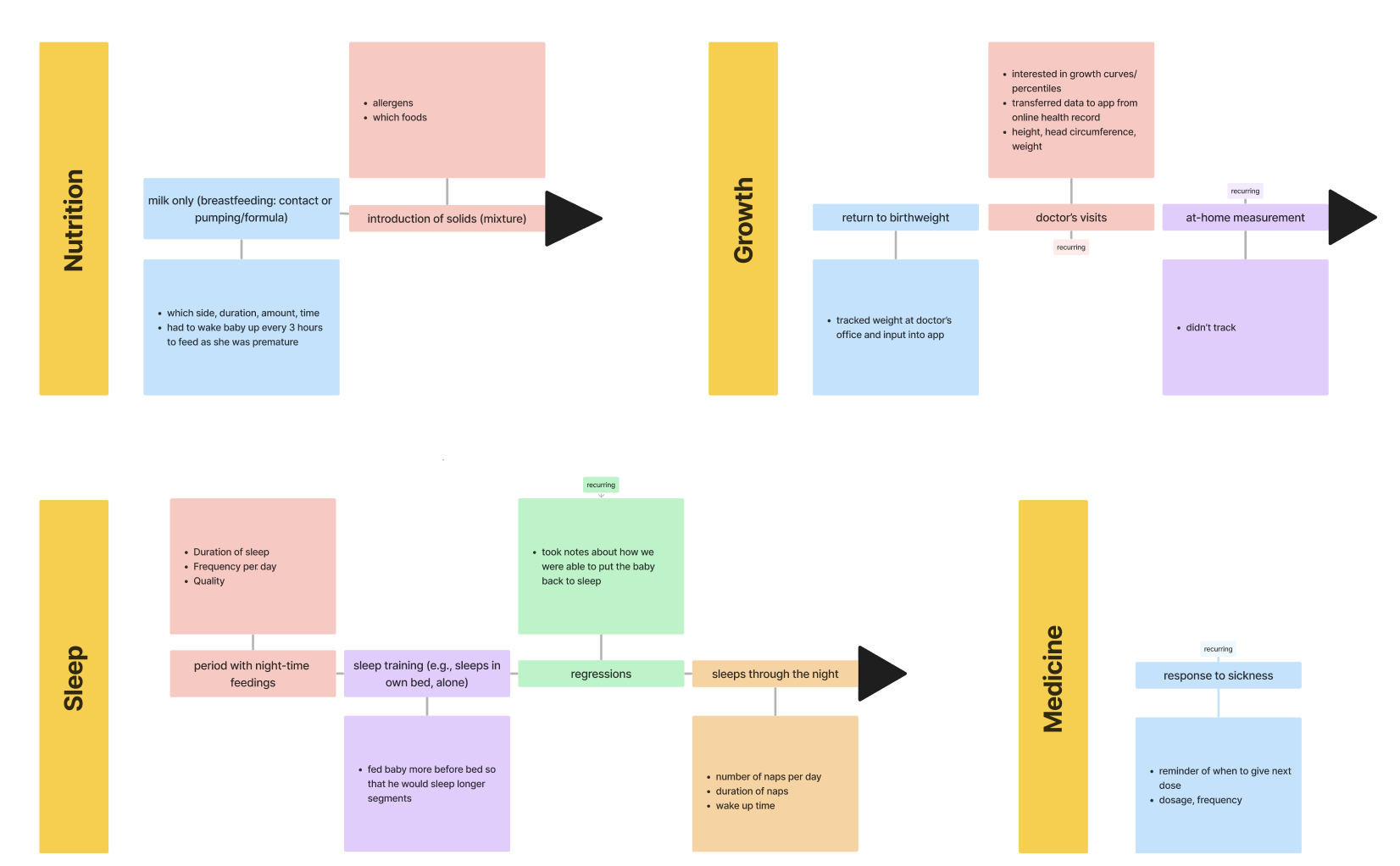

Baby tracking, the use of technology to monitor and reflect on the daily routines of babies, offers a useful case study of understanding temporality as a whole, as both short- and long-term reflection are commonplace. Therefore, we used baby tracking as a case study to explore how tracking technology can be applied for short-term reflection, enhancing our understanding of short-term temporality. After interviewing 20 parents and conducting a thematic analysis, we developed a framework outlining four distinct windows of short-term tracking:

1.

Immediate Window

Users reflect on data during or immediately after tracking. Reflecting immediately after tracking has been completed allows users to understand how much or how long of an activity they just completed.

In baby tracking:

In the baby tracking realm, people often reflect in this window to answer questions like 'How long has my baby been asleep' or 'How much has my baby eaten?'.

Applications in other domains:

Users tracking in other domains might have questions such as 'What is my current heart rate?' (fitness/health), 'What is my basal body temperature?' (fertility), or 'How long did I exercise for?' (fitness).

2.

In-Between Window

Reflection occurs between two instances of data collection, with the former (i.e. the last entry) being reflected on. This window is often utilized as a means of preparing oneself for the next tracking activity by reminding oneself of the previous one.

In baby tracking:

Common questions people tend to ask in this window include 'How long has it been since my baby ate?' and 'When did I last give my baby their medicine?'.

Applications to other domains:

'When was my last medication dose (e.g. insulin)?' (health, diabetes tracking) or 'When and how long was my last workout?' (fitness).

3.

Cumulative Window

Reflection happens on cumulative data collected during a specific time period. This time period is typically a day as humans naturally tend to structure their lives around the day, causing, for example, total-based goals to reset daily.

In baby tracking:

These total-based goals are often medically recommended causing parents to ask questions like 'How much did my baby eat today?' or 'How many wet diapers did we have today?'

Applications to other domains:

Users may ask 'How much water did I drink today?' (pregnancy tracking hydration levels) or 'How much medicine did I take (e.g. inhaler)?' (health). Some goals may not be medically recommended and instead could be self-imposed: 'Did I reach my sleep goal today?'

Our framework addressed the practical needs of users concerning short-term reflection and temporality, made theoretical contributions to the understanding of temporality in personal informatics, and identified new design opportunities for integrating user requirements related to temporality.

What I Learned during the Research Process

20+ hours of Interviews: Gathering Qualitative Data

During the project, I conducted over 20 interviews and cleaned a dataset of more than 500 rows and 2,400 lines of transcripts.

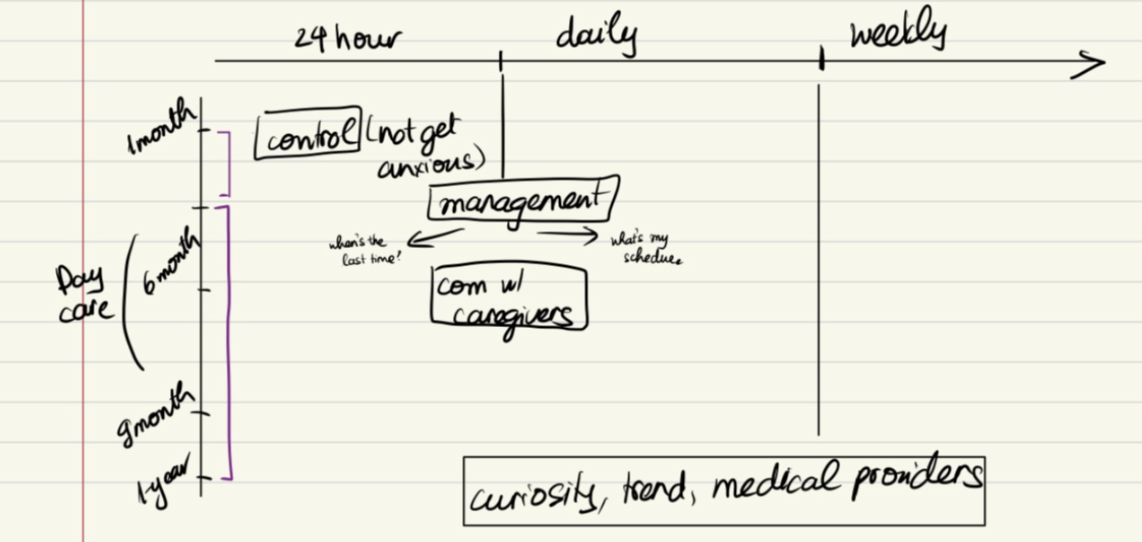

Putting ourselves in the shoes of parents with newborns, we understand how challenging it is to

remember all the details about tracking their babies' activities with their inconsistent

schedules. During the interview, we designed a timeline model using Figma to help guide our

participants in organizing their thought process.

While we offered some guidance on milestones and categories, we allowed the participants to

elaborate on what they tracked. These categories include sleep, nutrition, growth

(weight/height),

diapers, and medicine.

2,400+ Lines of Speeches: Turning Data into Thematic Analysis

After the interviews, I turned over 20 hours of recorded conversations into a thematic analysis. This process involved finding, coding, and organizing key themes from the data, which helped me extract meaningful insights from user experiences. Through this analysis, I learned to apply various UX research techniques, developing my ability to think critically about the patterns and themes that emerged.

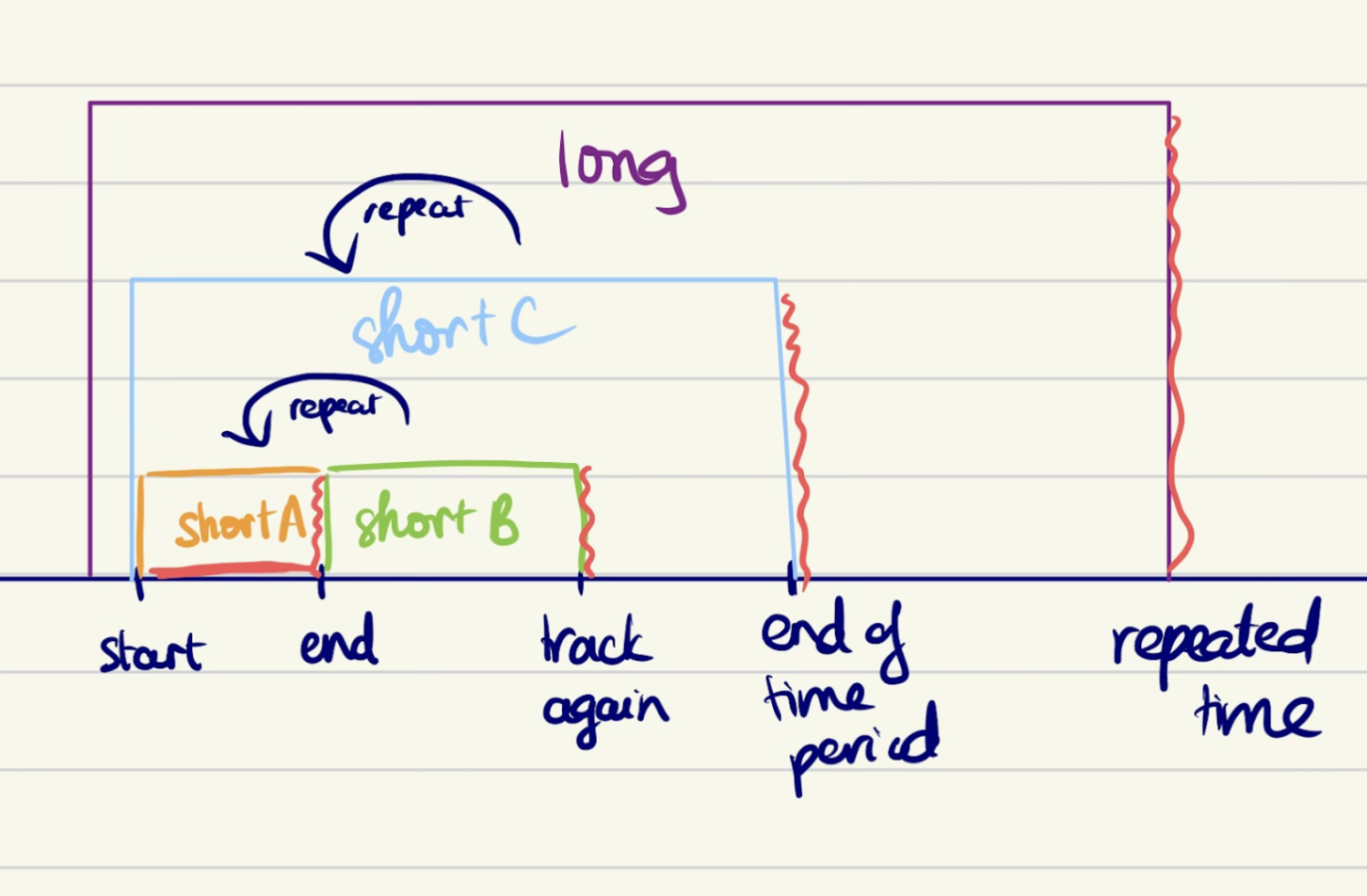

Visualization: Telling a Story

After conducting user research and literature review, we presented our findings visually with a model. The challenge was how to effectively deliver our ideas and communicate our discoveries.

My drafts in creating the temporarity model

More than Numbers - Gaining Insight into User Needs:

This research has been a defining project that inspired me to further pursue human-centered design. From conducting interviews to performing thematic analysis, I learned more than just research methods. It greatly deepened my empathy and understanding of users, emphasizing the importance of designing technologies that truly meet their needs. By putting myself in the users' shoes, I was able to identify a research gap, gained a new perspective on the challenges they face, and propose technology solutions to address those issues.

Research Poster Run-down:

Related Literature

[1] Ian Li, Anind Dey, and Jodi Forlizzi. 2010. A stage-based model of personal informatics systems. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '10). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 557–566

[2] Daniel A. Epstein, An Ping, James Fogarty, and Sean A. Munson. 2015. A lived informatics model of personal informatics. In Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing (UbiComp '15). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 731–742.